October 2025

Two worked tarsometatarsi of crane from Lower Austria

Even though it has only recently returned to Austria as a breeding bird, the common crane (Grus grus) belongs to the better documented avian species in the regional archaeological record, from the Neolithic up to the Late Medieval. Here, we present two worked tarsometatarsi of crane from Roman period contexts, which have recently become known to us. Cranes are large, long-legged birds – this becomes apparent in dimensions and proportions of the bones of their appendicular skeletons as well.

Photos: Günther Karl Kunst

The first specimen is from a Late Roman inhumation burial. According to anthropologic information provided by Ulla Steinklauber, it is from an early adult woman. The artefact was situated between the lower legs of the individual. This grave belongs to a larger cemetery at Stollhofen near Traismauer/Augustianis, one of the auxiliary forts with a vicus along the Danubian Limes in Lower Austria (district St. Pölten). The tarsometatarsus, from the right bodyside, is complete for most of its length, but some substance has been removed from the proximal part and the distal articulations. With a reconstructed total length of about 240 mm, it is comparatively small and slender for a common crane, but still inside the recent variation. There is a recent fracture in the middle of the shaft, which was partially restored.

The most apparent anthropogenic modifications are ring-and-dot motifs present on all four sides of the diaphysis. Apparently, these were produced by the same tool and exhibit outer diameters of about 5,7 mm. There are 12 ornaments on the lateral side, the most proximal, however, is incomplete. On the plantar surface, we observe only 2 motifs, accompanied by a „test boring“ more proximally. Medially, twelve motifs are arranged rather regularly along the central section. The most proximal appear rather deep or were widened after the drilling process. The dorsal aspect presents a series of eleven, rather crowded motifs, which were well executed, only some circle segments remained incomplete. The number and arrangements of the motifs appear to be largely determined by the morphology of the bone surface – only plane regions could be used. This becomes especially apparent on the dorsal side, where the proximal furrow was avoided. On the plantar side, the only available plane surface sections were chosen, with mixed success. Nevertheless, it may seem tempting to attribute a semantic meaning to the numbers and arrangements of the motifs. A long die, however, can be excluded for mechanical reasons. It should be mentioned that two bone bracelets on the left arm of the skeleton are also decorated with ring-and-dot ornaments.

At a closer look, it is evident that wider areas of the bone surface had been carved with a very fine blade, before the ring-and-dot motifs were added. There are also fine transverse cut-marks on the dorsal side of the distal articulation. Obviously, the bone was cleaned from soft tissues and intensively smoothed before it was decorated. There is also polish on the surface of the shaft, especially on raised ridges and exposed edges, whereas the lower-lying motifs and the distal area are less affected. Repeated handling is, therefore, indicated.

By coincidence, another worked crane tarsometatarsus has become known to us recently. It was found in the Roman settlement of Fischamend, which is located just east of today’s Vienna International Airport (district of Bruck an der Leitha, Lower Austria). The object was recovered from a large pit-like structure initially interpreted as a natural alluvial deposit. Due to the number of artefacts recovered from this context, it is more likely that it was connected to waste disposal activities on the site. The context dates to the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD.

The artefact was fashioned from the left tarsometatarsus of an adult common crane (Grus grus). The proximal end – the part of the bone closest to the animal’s body – and the medial trochlea – which connects the animal’s leg to one of its toes – were broken off before discovery. A sequence of fine cuts can be observed on the bone: The distal end right before the foot-joint shows cut marks parallel to the bone’s axis, while on the proximal end close to the fracture some fine crosscuts can be noted. These likely suggest a meticulous defleshing of the bone prior to usage. However, the most striking anthropogenic alterations of the object are the perforations of the trochlea. The lateral trochlea was perforated in dorsoplantar direction – so from front to back – and the middle trochlea along the transversal axis – meaning from side to side. Whether the medial trochlea was also perforated is unclear, because it isn’t extant anymore. Almost the entire distal part is covered in green copper-alloy patina, which suggests the presence of metal attachments. The shaft of the bone is well polished, which can be seen as a sign of frequent handling. The holes could have been used to hang the bone, or more likely, the bone might have functioned as the shaft of a rattle- or whip-like item.

Olivér Borcsányi and Günther Karl Kunst

September 2025

An ornamented carapace from the Mesolithic

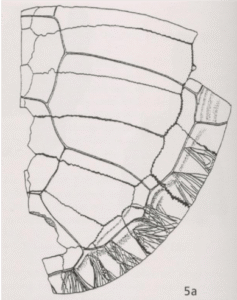

At the Mesolithic site of Friesack in Brandenburg, northeast Germany, an extraordinary find was made during excavations in the 1980s: a carapace engraved with triangular patterns. It belonged to a European pond turtle (Emys orbicularis) – this species spread over large parts of Europe after the last ice age.

Friesack was a camp site, which was periodically inhabited in the Mesolithic from the Middle Preboreal, approx. 9200 cal. BC, up to the mid-Atlantic, about 5600 cal. BC. by hunter-fisher-gatherer groups. The landscape, formerly characterised by water areas, mixed forests and open land, offered perfect living conditions for humans and numerous animal species. Of the countless artefacts made of flint, bones and wood excavated there, 18 were intentionally engraved.

In Europe a carapace with incised patterns is known from only one other site in southern Sweden. From the carapace, which is dated into the late Atlantic by pollen analysis of the adhering peat residues, 2 fragments with scraped out insides have been preserved. The larger fragment, belonging to the right side of the carapace, has a length of 11.2 cm. On its outside, at least seven triangular figures were incised along the edge, with indications of an eighth figure.

The smaller fragment, belonging to the left side of the carapace, has a length of 4.7 cm. Carved in it were 4 to 5 long triangular figures merging into one another, which could possibly be stylised representations of humans depicted in profile – however, interpretations of the carvings are highly speculative because their meaning can no longer be deduced. Due to the fragmentation, it unfortunately remains unclear to what extent the remaining carapace was also provided with engravings.

There are various considerations for the function: carapaces scratched out on the inside were possibly used as small containers or as tools for digging pits or drawing water. Due to the ornamentation, the carapace also could have had a ritual meaning and was maybe used as jewellery or as a kind of amulet.

Julia-Sophie Meier

From top to bottim: outside and inside view of the carapace fragments; detailed view of the carvings on the carapace fragments; the sketched fragments of the carapace with the carvings.

References:

• Gramsch, Bernhard (2000): Friesack: Letzte Jäger und Sammler in Brandenburg. – Jahrbuch des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums 47, 51-94

• Gramsch, Bernhard (2018): Mesolithische Knochen- und Geweihartefakte mit intentionellen Ritzungen von Friesack, Fundplatz 4, Lkr. Havelland. – Veröffentlichungen zur brandenburgischen Landesarchäologie 48, 7-54

August 2025

In 1983 a bovid femur was excavated from 7000-year-old deposits at Kruger Cave, South Africa. What made this femur unique was that embedded inside the marrow cavity were three modified bone points. Similar bone points are widely considered to have served as arrowheads, which makes this find the only known femur quiver on record in sub-Saharan Africa.

This artefact was recently revisited with the aim of analysing the matrix in which the bone arrowheads had been embedded. Computed Tomography scans had shown that this matrix was clearly not part of the bone and was inconsistent with the sediment from the site. Results from GC- and LC-MS analyses confirm that this material is of plant origin and contains two different cardiac glycosides (heart toxins) and the byproduct of a toxic lectin. These three compounds do not occur in the same plant, indicating that people were combining different plant taxa together into a complex poisonous recipe. This is the oldest chemically verified evidence in the world of a multi-ingredient poison recipe.

Furthermore, none of the plant taxa in which these compounds occur grow in the vicinity of the cave, neither now nor in the past. This would suggest that people 7000 years ago were either traveling quite some distance to collect specific plant ingredients to make this poison cocktail, or that long-distance exchange networks existed at this time. Either way, these findings add to our understanding of the antiquity of traditional pharmacological knowledge systems.

Justin Bradfield

References:

• Bradfield, Justin / Dubery, Ian A. / Steenkamp, Paul A. (2024): A 7,000-year-old multi-component arrow poison from Kruger Cave, South Africa. – iScience 27(12) 111438

July 2025

Mysterious Lead-Filled Horse Bones from a Roman Temple Site

Location: Herwen-Hemeling, The Netherlands

Date: 1st–4th century CE

In 2022, archaeologists uncovered a significant Roman cult site in Herwen-Hemeling, near the modern-day Dutch German border. Used primarily by Roman soldiers between the 1st and 4th centuries CE, the sanctuary featured at least three temples and many other kinds of cult buildings. One of them was a Gallo-Roman style temple with an enclosed gallery or ambulatory (a so-called “omgangstempel”), decorated with painted walls and a tiled roof. Two other, smaller temples also showed traces of painted plaster. Among the votive stones discovered were inscriptions dedicated to Hercules Magusanus, Jupiter-Serapis, and Mercury.

Among the many remarkable finds were two horse bones filled with lead. These metatarsal bones – or cannon bones – are an enigmatic discovery.

Two Bones, Two Temples

The bones were not recovered as a pair. They were found in separate locations within the temple complex — one next to the large stone temple, the other near a smaller shrine, about 60 metres away. This spatial separation suggests that the bones were not deposited together, but each in a distinct context.

Close Inspection: Craftsmanship and Use

One of the bones was broken upon discovery, allowing for detailed examination. The proximal end – the part nearest to the horse’s spine – has been carefully drilled to create a cylindrical shaft, which was then filled with molten lead. The resulting lead rod inside consists of three equally sized segments. This suggests that the bone was filled in stages — likely using a small crucible, with each pour cooling before the next was added.

The best-preserved bone offers further clues. Its proximal end — the side closest to the horse’s body — appears smoothed and worn, possibly from use. Prior to the lead casting, the bone was flattened and polished with skill. The wear could reflect both the manufacturing process and later handling. The surface has a subtle shine, and one end displays a thick plug of solidified lead.

What Could They Be?

Lead-filled animal bones are rare in archaeological contexts, and their function is still unknown. A similar bone was found at a presumed Roman site in Goedereede, in the southwest of the Netherlands. Unfortunately, that bone was found out of context, making interpretation even more difficult.

Inquiries among colleagues have not yielded any closely comparable finds. Could these have been weights? Ritual objects? Sounding tools? So far, we remain in the dark.

Can You Help?

Have you seen a similar object or have an idea about the purpose of these lead-filled horse bones? Please get in touch with

E. Norde (RAAP Archaeological Consultancy) or Joyce van Dijk (Archeoplan Eco)

June 2025

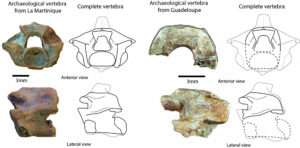

Worked Snake Bone Beads

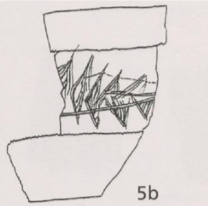

Finds of worked snake bone are a rarity worldwide. That makes the eight worked Boa vertebrae from the Lesser Antilles even more notable. During excavations between 1989 and 1992, seven rounded and polished vertebrae were found in Dizac Beach on Martinique Island. One more was found during excavations of the Basse-Terre Cathedral on Guadeloupe Island. All date back to the Saladoid culture, between 2500 cal. BP and 1500 cal. BP, when some Boa species likely still inhabited the Lesser Antilles. Today, most of these species, excluding the still surviving Boa nebulosa and Boa orophias, are extinct on the islands and are only known through the fossil record.

On the vertebrae, where it was possible to observe, the dorsal and ventral sides were rounded and polished, and the neural spine, prezygapophysis, as well as the hemal keel, were either removed or reduced to varying degrees. The seven vertebrae from Dizac Beach were in relatively bad shape compared to the partial vertebra from Basse-Terre, and it is difficult to discern how much the lateral parts of the bones have been manipulated. Overall, the vertebrae from the two locations showed similar modifications, but to differing extents.

Thanks to their size and characteristic shape, the bones could be specified as belonging to a species of Boa, but sadly, it could not be determined which one. All modifications had to have been made by human hand, with the purpose of the bones appearing as a sort of bead or amulet, exploiting the large nerve canal in the vertebra for ease of possibly stringing the pieces on a rope or thread. The beads could have been used as jewellery but also may have been an object of belief, explaining the unusual choice of animal used. Since these snakes are not a common source of meat and are not a great threat to livestock or humans, they are rarely hunted and killed. It is, as such, very unusual to find their bones in anthropogenic contexts outside of coincidences. Quite the opposite, snakes, especially Boa and Python, have in the past often been viewed as sacred or have been feared for other supernatural reasons, lending credibility to the thought that the bone beads from the Lesser Antilles were objects of belief to some extent.

Anna Buderer

Two of the vertebrae found in Martinique and Guadeloupe, with reconstructions of the complete vertebrae; photo: Corentin Bochaton, Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology 2020.

References:

• Bochaton, Corentin (2020): First records of modified snake bones in the Pre-Columbian archaeological record of the Lesser Antilles: Cultural and paleoecological implications. – Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology 17(1), 126-141

• Thorpe, R. S. & Malhotra, A. (2023): Systematics and biogeography of snakes of the genus Boa in the Lesser Antilles. – Caribbean Herpetology 88, 1–14

May 2025

Front and back of the fibula made of ivory from the Artemision of Ephesos (ART 870357); photos: J. Wurzer ©ÖAI/ÖAW

The double-disc or spectacle fibula made of ivory derives from the Archaic Artemision of Ephesos. It was found in the western part of the cella of Naos 1 and – based on the stratigraphy – dates around the middle of the 7th century BC. The fibula is part of the extremely rich votive offerings made of various materials found in the Artemision.

The artefact consists of two discs, each decorated with concentric circles, between which are eleven smaller circles with a centre point. The connecting piece between the two discs is also decorated with circular dots. At the semicircles top and bottom, there are remains of small holes with bronze residue. Both discs are pierced in the centre, and the holes still contain remnants of bronze nails or pins. On the back, the corroded bronze remains of the former fibula pin and its holder are visible. The fibula is polished and has a greenish colour due to the oxidation of the bronze nails.

A total of about 20 fibulae of this type are known from the Artemision. They are between 4 and 6 centimetres in size, the motifs can vary with different arrangement and number of circles.

Double-disc or spectacle fibulas are known from numerous early Greek sanctuaries throughout the Mediterranean region, where they were deposited as votive offerings or gifts to the respective deity

Andrea M. Pülz

References:

• Rizzo di Vita, Maria Antonietta (2024): Ossi. in: Livadiotti, Monica (ed.): Ialiso II. Il sanctuario di Athana Polias a Ialysos (Rodi), 691-721, Athen

• Seipel, W. (2008): Das Artemision von Ephesos. Heiliger Platz einer Göttin, Ausstellungskatalog, Wien

April 2025

Carnet de bal (dance booklet) made of bone and ivory (19th century)

Here’s an almost complete 19th century handcrafted object that will become part of the ethnographic collections of the Musée de l’Homme. According to the owner’s family history, it dates back to the Tsarist times, when upper-class women used to write down the names of the dancers to whom they reserved their next dances. This “Bal” book, as written in French on the ivory cover, is made up of 5 bone cards, each for the five expected dances: waltz, polka, mazurka, quadrille and galop. The back is probably made of bone to implement the metallic fastening system that held the missing graphite tip in place. Suspended from a ring and riveted in such a way that the silk passementerie opened the rough bone blades like a fan, the whole was used to hang on the ladies‘ ring finger.

So chic, isn’t it?

Éva David

March 2025

Two human bone koauau (flute)

The old Maori flute from a femur is from early 19th century, carved with iron tools. After the family member died, 12 to 18 months later the skeleton was cleaned / scraped and sometimes painted with kokowai (red ochre paint), then a femur was taken to be turned into a flute. The remaining bones would be hidden away in a cave or hollow tree. This was a way to keep the memory of the deceased and history alive. The flute would be considered very tapu (sacred). On the other hand an enemy’s femur could be taken for a flute as an insult and ongoing irritation to that tribe, probably of a famous warrior so the stories of his death and battle would be passed down. Often that flute would be ransomed back to bring peace between the two tribes.

The contemporary flute is from a Maori who lost a leg in a forestry accident. He asked me to carve a flute from his femur so he had a memory of the occasion and something to leave his family passing on his stories.

Dimensions: old flute 185 mm long, contemporary flute 160 mm long.

All my carving is executed with hand gravers or burins, which I make from tool steel. Basically, my gravers are copies of Neolithic flint gravers with short wood handles based on examples from Danish Museum collections. So I carry on the carving skills, techniques and philosophy of my ancestors.

Owen Mapp

February 2025

Above illustrated is a giant sloth tooth (Eremotherium laurillardi) from the Pleistocene of Brazil (dated to ca. 14-13,000 years ago). It was found in Sergipe state, northeast of Brazil, in a „tank“ fossiliferous deposit. Its current shape (triangular) is completely different from the original shape of ground sloth teeth (cylindrical). In addition, one side is polished and presents several marks that we interpret as anthropogenic due to their clusters of similarly sized scratches, following the same orientation, especially around the curvature of the tooth.

Thais Rabito Pansani

References:

• Pansani, Thaís Rabito / Bertrand, Loïc / Pobiner, Briana / Behrensmeyer, Anna Kay / Asevedo, Lidiane / Thoury, Mathieu / Araújo-Júnior, Hermínio I. / Schröder, Sebastian / King, Andrew / Pacheco, Mírian L. A. F. / Dantas, Mário A. T. (2024): Anthropogenic modification of a giant ground sloth tooth from Brazil supported by a multi-disciplinary approach. – Scientific Reports 14 (19770)

January 2025

Early medieval saddle decoration made of antler plates from a woman’s grave in Bavaria

In the mid-1990s, a looted chamber grave of a woman buried with her mule was discovered in Aufhausen/Bergham (Erding, Germany). A separate compartment of the burial chamber was disturbed but escaped robbery. In it, the almost intact bone fittings of a saddle bow were found in situ, as well as other fragments of bone fittings belonging to the saddle. The finds are complemented by a richly decorated snaffle bit made of iron and bronze, a number of magnificent bronze and silver fittings from the bridle and other horse tack, as well as iron buckles from saddle girths and bridle. The metal fittings of Frankish origin allow dating from the late 7th to early 8th century.

At the beginning of the 2020s, these finds could be examined more closely, which led to the conclusion that the lady was buried with not just one but two saddles both decorated with antler plates from red deer. The dimensions of the fittings on the saddle’s front arch (fig. 1) as well as the corresponding fragments of the rear arch and the wings belonging to this saddle conclusively show that this is a women’s sideways saddle for a mule (fig. 2-3). The fittings of the second saddle indicate a conventional riding saddle in the style of the steppe nomads (fig. 4). Whereas the decorations on the latter saddle represent a variant of the interlace ornament common in Avar as well as Old Turkish culture, the combination of interlace ornament and floral patterns on the women’s saddle is puzzling. It is assumed that it originated „between Friuli and Lake Balaton“.

Bone fittings on saddles have a long tradition in the equestrian nomadic environment and are mainly known from the Avars in Merovingian Europe. They are a rare find in Western Europe, in this case possibly helped by the calcareous alpine “alm”-soil in which the grave was dug, which is favourable for preservation.

Dimensions of the front saddlebow: height 30 cm, depth 0,1-0,2 cm, width 30 cm.

Bettina Keil-Steentjes

Fig. 1: front bow of the sideways saddle; fig. 2: reconstruction of the sideways saddle; fig. 3: in the sideways saddle, both legs of the rider are on one side of the mount; fig.4: antler plates of the second saddle with interlacing pattern (Photos: Harald Krause, Museum Erding).

References:

• Keil-Steentjes, Bettina & Päffgen, Bernd (2024): Das Reitzeug aus dem spätmerowingerzeitlichen Kammergrab der Dame von Aufhausen/Bergham (Stadt Erding). – Archäologisches Korrespondenzblatt 54, 51-74

• Paulus, Christof / Nadler, Michael / Ketzer, Christine / Andres, Won / Handle-Schubert, Elisabeth / Jörgensen, Bent / Lichtl, Julia / Scherrer, Andreas / Zödi-Schmidt, Natascha (2024): Tassilo, Korbinian und der Bär. Bayern im frühen Mittelalter. – Veröffentlichungen zur Bayerischen Geschichte und Kultur 73, 196-199

Bonetool of the Month Archives

- 2024

- 2023

- 2022

- 2021

- 2020

- 2019

- 2018

- 2017

- 2016

- 2015

- 2014

- 2013

- 2012

- 2011

- 2010

- Table of bonetools 2010-2022